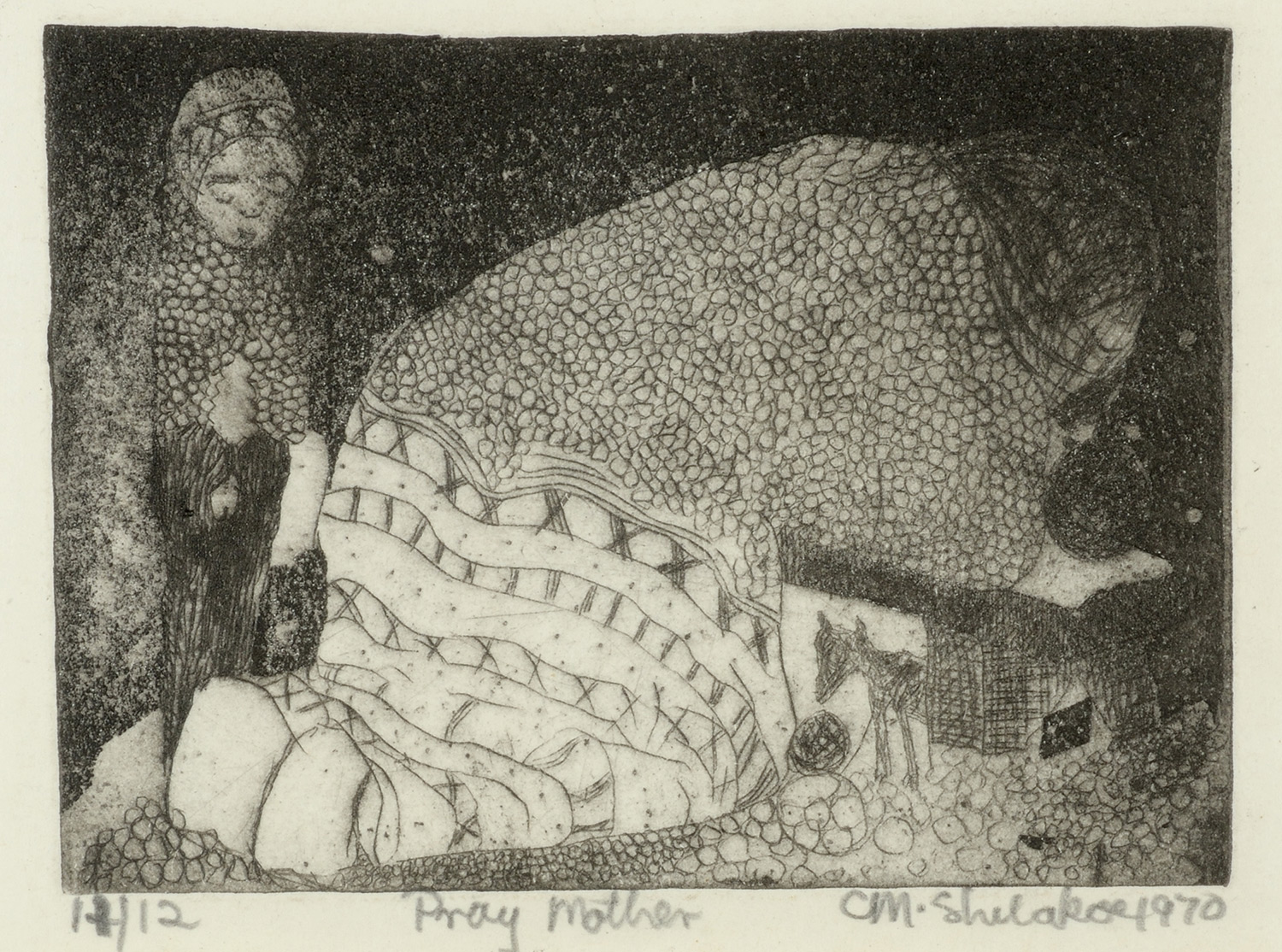

Cyprian Mpho SHILAKOE (1946 – 1972)

Pray Mother

1970

dry point etching

edition 11/12

9.5 cm x 13 cm

A woman is bent over in prayer as her young child looks on. The intricate detail of Shilakoe’s mark-making is evident in the patterns of the cloth in which she is draped. The mood is sombre, and the delicacy of lines and textures adds to the tenderness of the moment captured. A small animal in the light of a doorway appears peers in on the sad scene – another tender feature of this poignant work

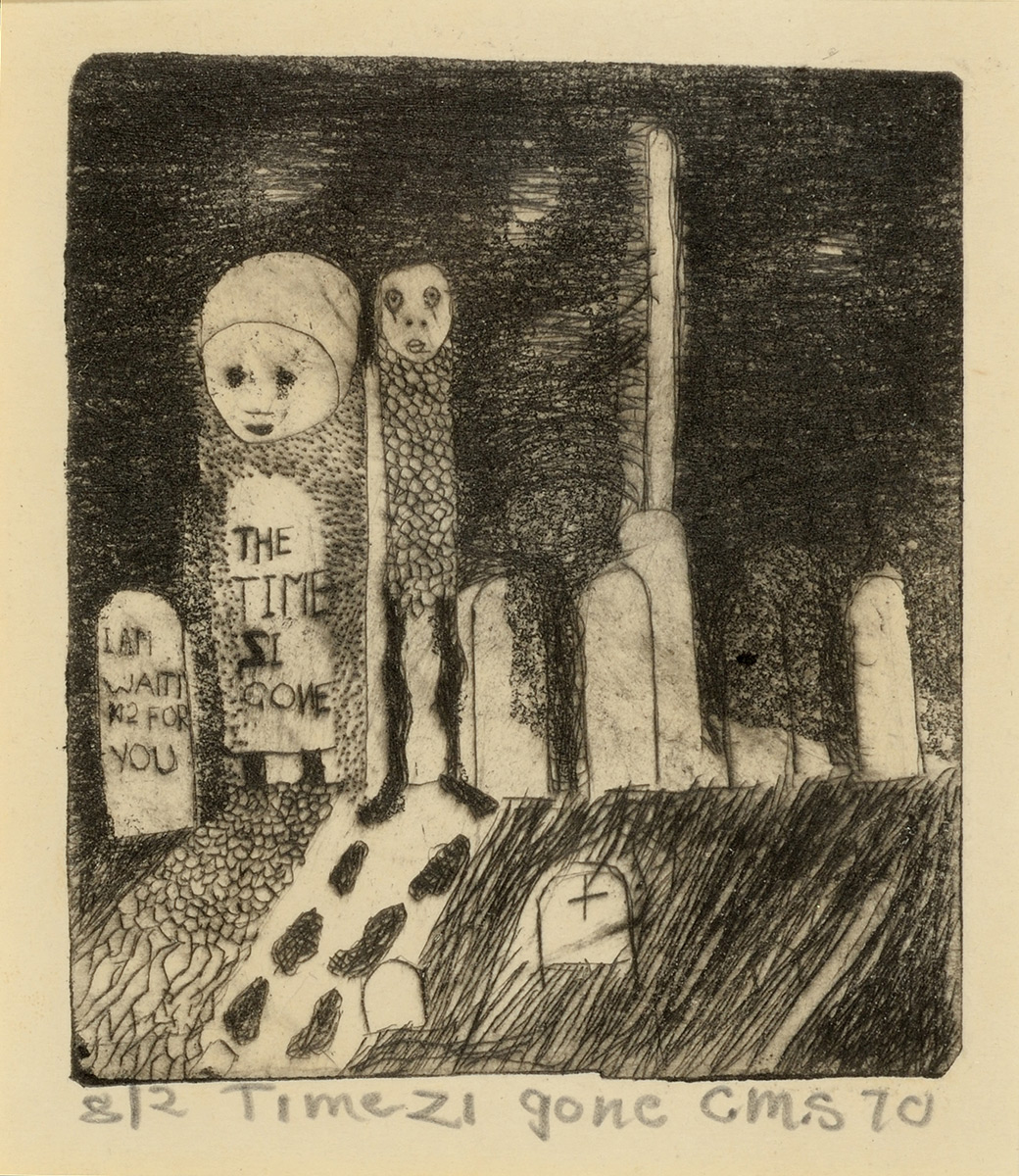

The Time Is Gone

1970

dry point etching

edition 2/8

11 x 9.4 cm

In this solemn work, two mourners hover in the scarcely illuminated darkness of a cemetery, paying respects to their dear departed. The wording on the tombstones is a reminder of the mortality of the living, and the figures seem haunted by their own footsteps even.

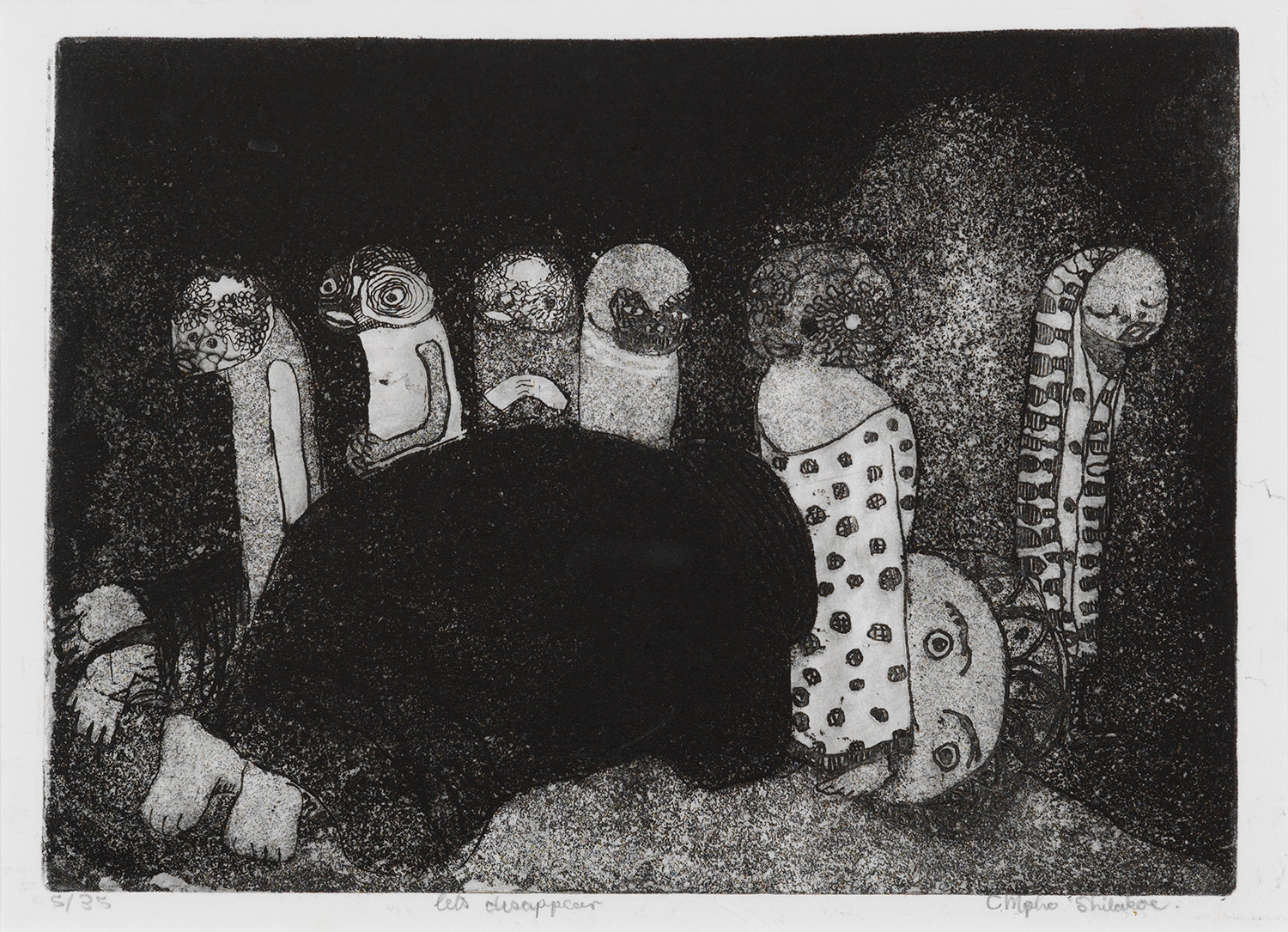

The Time Is Gone

1970

dry point etching

edition 2/8

11 x 9.4 cm

A figure lies prostrate overcome by six diminutive hovering beings, who although partly human, are also of another world. Cocoon-like and mildly reptilian, their presence is imbued with a liminal threshold quality. The absence of visible limbs gives a sense that the central figure is immobilized by the presence of the small figures, one of whom appears to be passing right through him. In this depiction of a metaphysical state of transition, nothing is quite as solid as it seems.

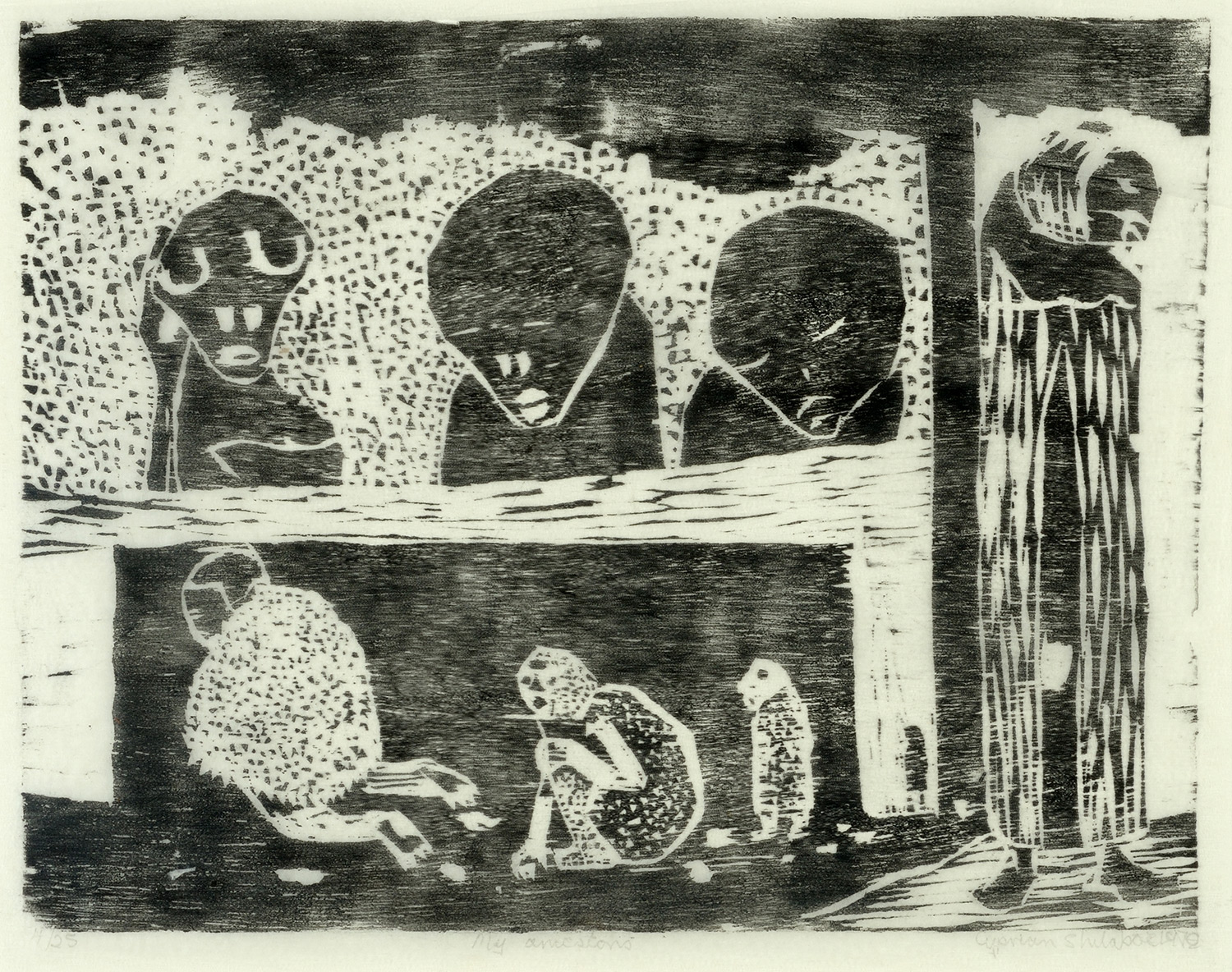

My Ancestors

1970

woodcut print

edition 4/25

30 x 39 cm

The textured grain of the wood comes through in this complex work in which the artist depicts a state of communion/dialogue with his ancestors. The mood is doleful and fraught. The three faces in the foreground appear to be looking downwards, reflecting on the actions of the small figures below – the ancestors watching over the actions of the living perhaps. The small figures huddled in the foreground appear to be playing with stones – or are they throwing the bones to access the advice of the ancestors? The image is broken up into three geometric plains, the figures each occupying a separate plain of the picture. A tall, cloaked authority figure with a stern face stands in the light of the doorway looking outwards towards the light. Is this figure standing guard or keeping the other figures captive? It is impossible to say. This is the mystery of the work.

My Childhood Remembrance

1970

woodcut print

edition 7/25

30 x46 cm

In this poignant self-portrait, the artist projects himself back into his own childhood. A small figure labours under the weight of a large black log. On closer observation, it appears that child is not entirely human. Birdlike, he perches on the fence – hands for claws. His face and body are covered in scales, giving him a shape-shifting, creature-like appearance. It is also possible that he is resting on the shoulders of another figure, crouched between his legs. The sharply delineated black-and-white background planes give the sense of a harsh, brittle environment in which the small hovering figure is overcome by a sense of being strange and other.

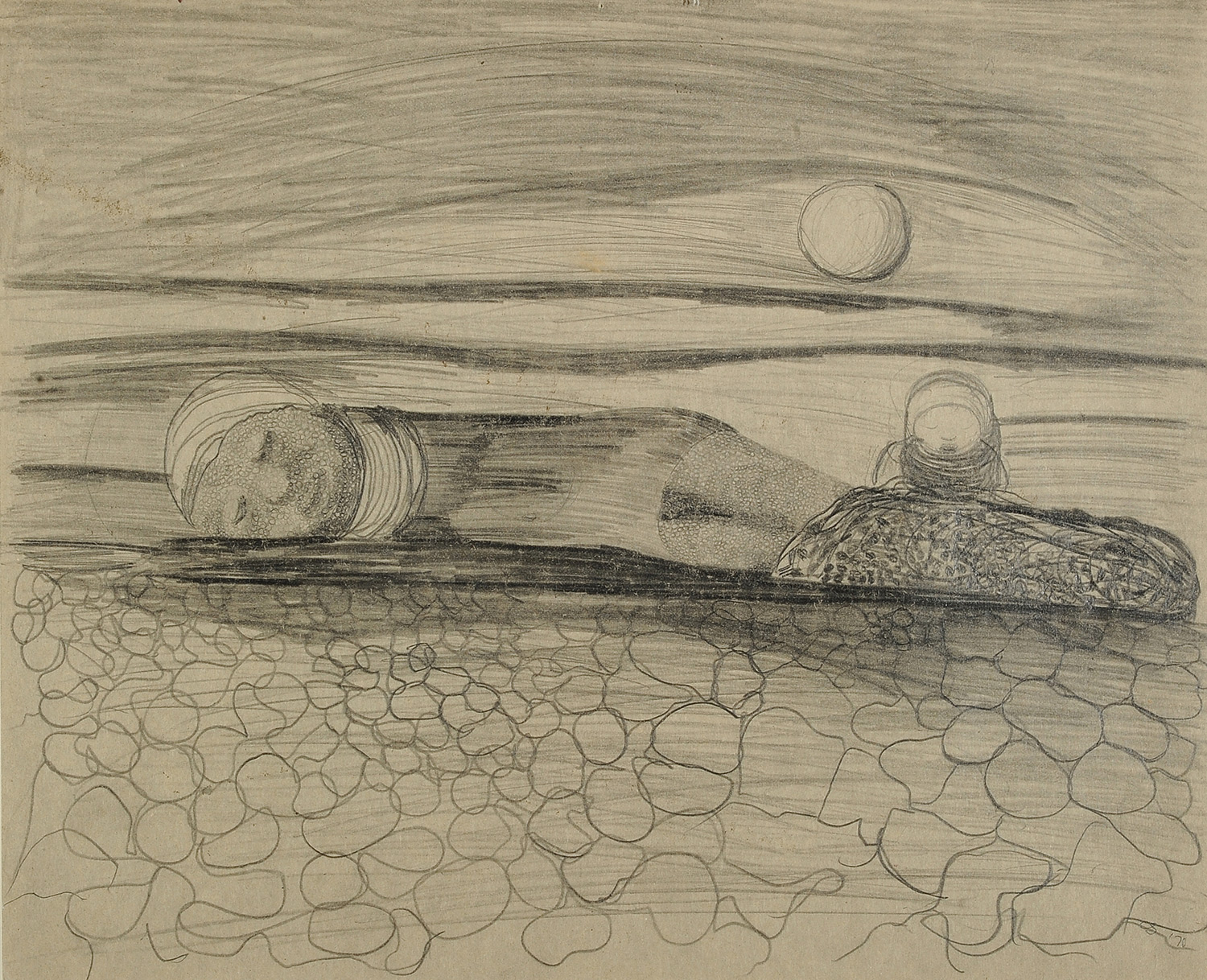

She Is Sleeping

1970

pencil on paper

37 X 46 cm

A small childlike figure hovers over the prone body of a woman. The full moon echoes the shape of the child’s head.

‘Shilakoe’s childhood was marked by an early loss: the death of his grandmother, whom two-year-old Shilokoe was sent to live with in 1950,’ writes Mary Corrigal. ‘According to Mahlungu [Shilakoe’s sister], Shilakoe was devastated by her death; he thought of her as his mother. His grief however, found a productive outlet in art, which he took up after her death. He was 16 when he returned to live with his parents at the Dennilton [Mpumalanga] home. Mahlungu noticed early on that Shilakoe was an unusual personality. He shied away from other children, preferring to immerse himself in making art. His artistic talent was obvious to all and caught the attention of his teachers at Paledi Secondary School, who advised his parents to take him to an art school. Soon after, Shilakoe was introduced to [Dan] Rakgoathe, a school teacher and artist. Rakgoathe encouraged… Continue Reading

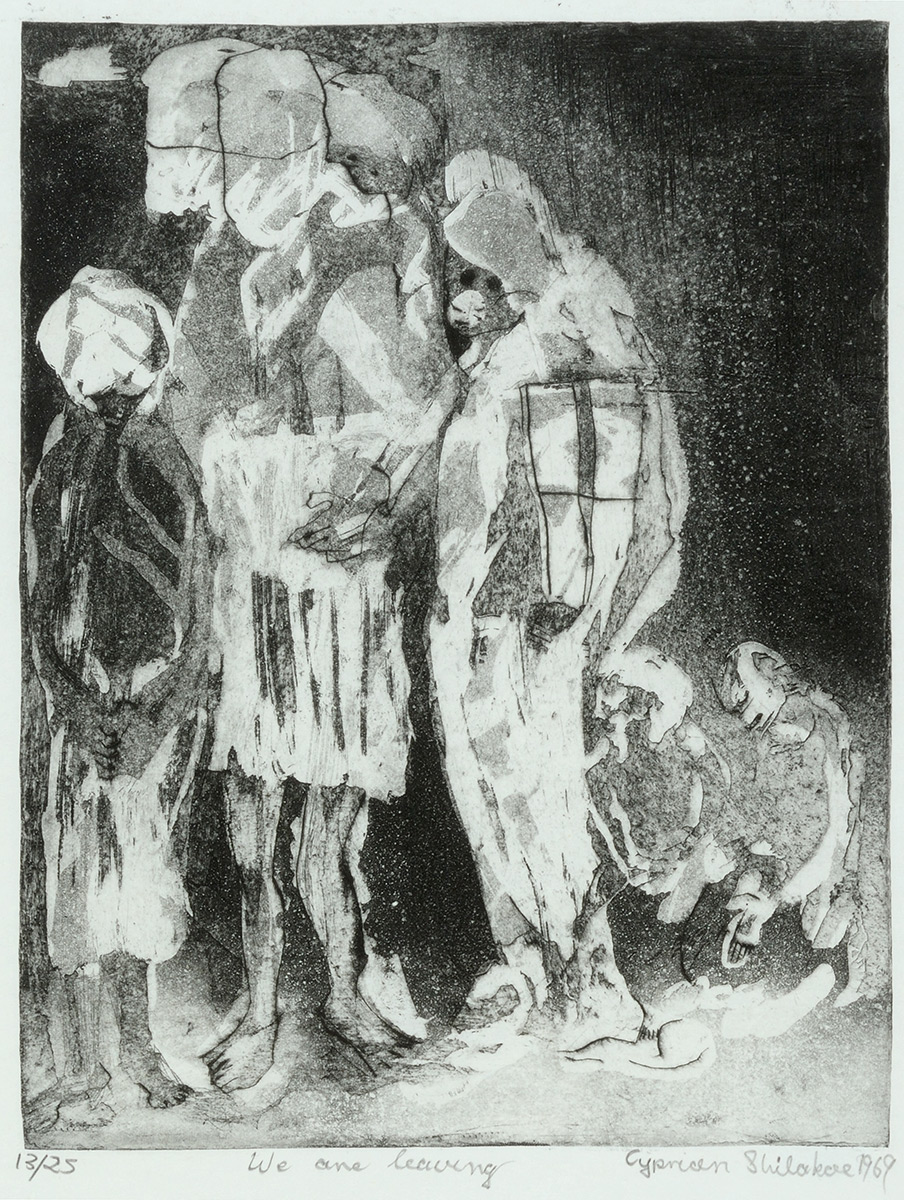

We Are Leaving

1969

etching

edition 13/25

27 x 31 cm

In this characteristically moody work, a family huddles sadly together in a moment of leave-taking or departure. The title indicates that they are going somewhere, but they are barefoot, which makes them seem ill-equipped for the journey ahead. The heads of the figures in the background are turned despondently downward.

‘The atmospheric, dream-like effect in Shilakoe’s work is achieved by his masterly use of aquatint. Instead of using it in large, tonal areas, he preferred to apply the aquatint selectively, resulting in the rich, lustrous quality of his prints,’ writes Joe Dolby.

SOURCE:

http://www.revisions.co.za/biographies/cyprian-shilakoe/#.VRMMTULlelI

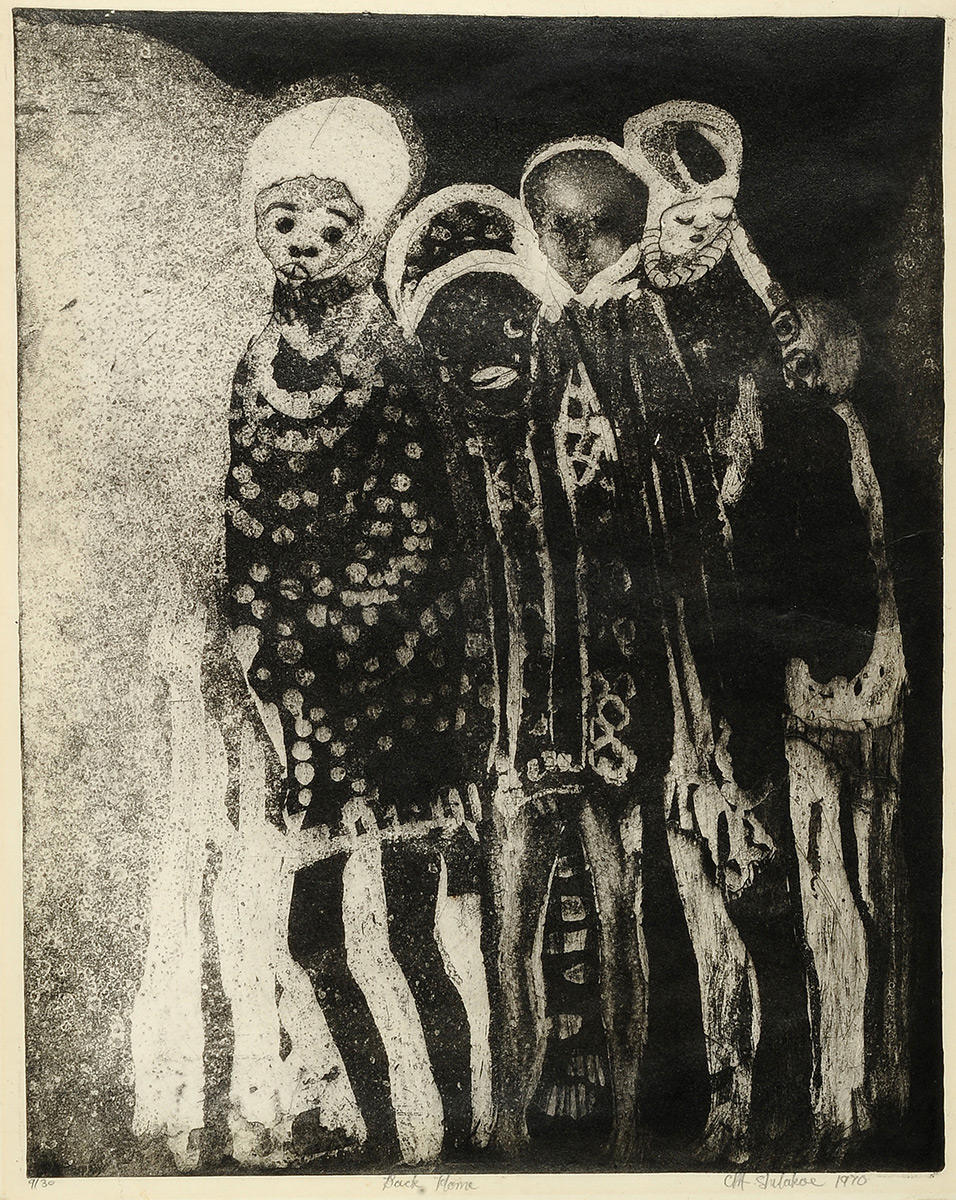

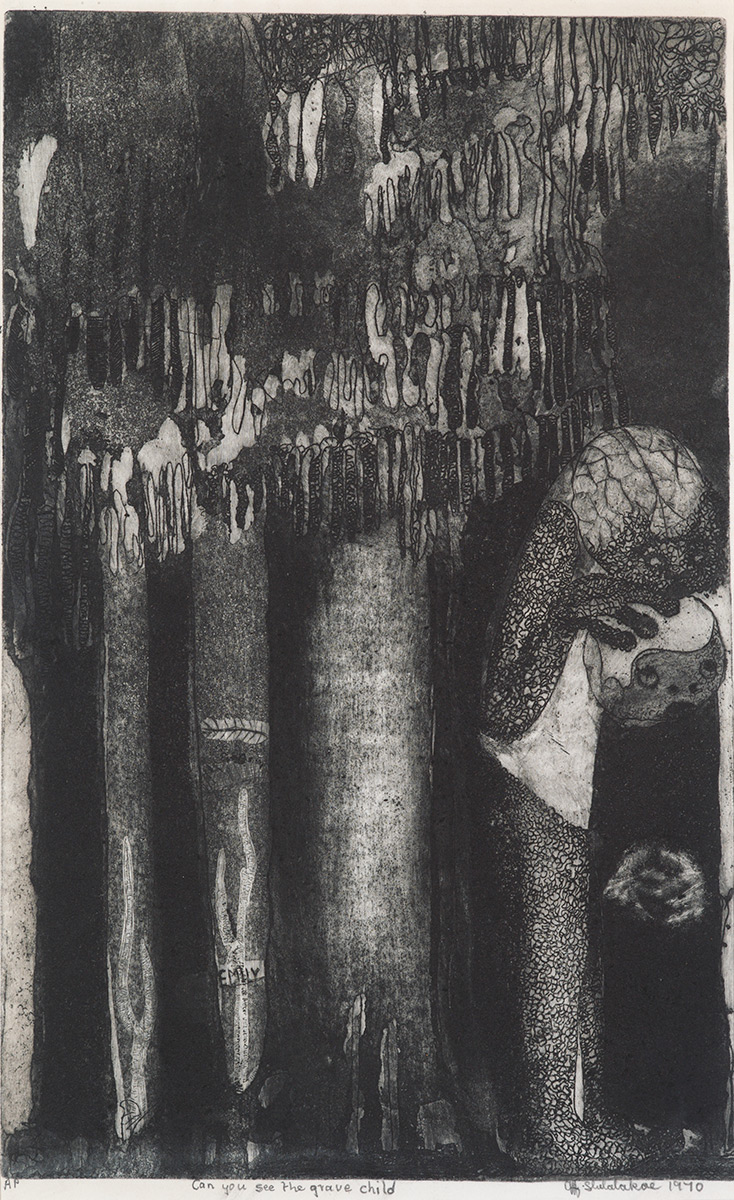

Can You See The Grave Child

1970

etching

edition AP

37 x 23 cm

In this foreboding and somewhat gothic etching, a childlike figure is overcome by a reptilian form, which hovers over him in a dark, cavernous setting. A strange substance seems to be falling from above, recalling overhanging vegetation in the depths of a forest or the stalactites in the interior of the Cango Caves. The title indicates that this is a depiction of a moment of premonition.

In her opening address in July 2002, Jill Addleson, curator of the exhibition ‘Cyprian Shilakoe Revisited’ commented: ‘Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of all was that he actually visualized his own death, but assured his sister, Emily, that he wasn’t upset about this as he was “… going to leave this world, but I will be back … in a way you don’t understand”. What makes the account even more graphic is that other people who were close to him also experienced premonitions of his death. They included Dan Rakgoathe, his great friend, Otto Lundbohm his teacher, the artist, Louis Maquubela, and his sister, Emily. There is no doubt that his very early death robbed our country of one of its most original and powerful artists.’

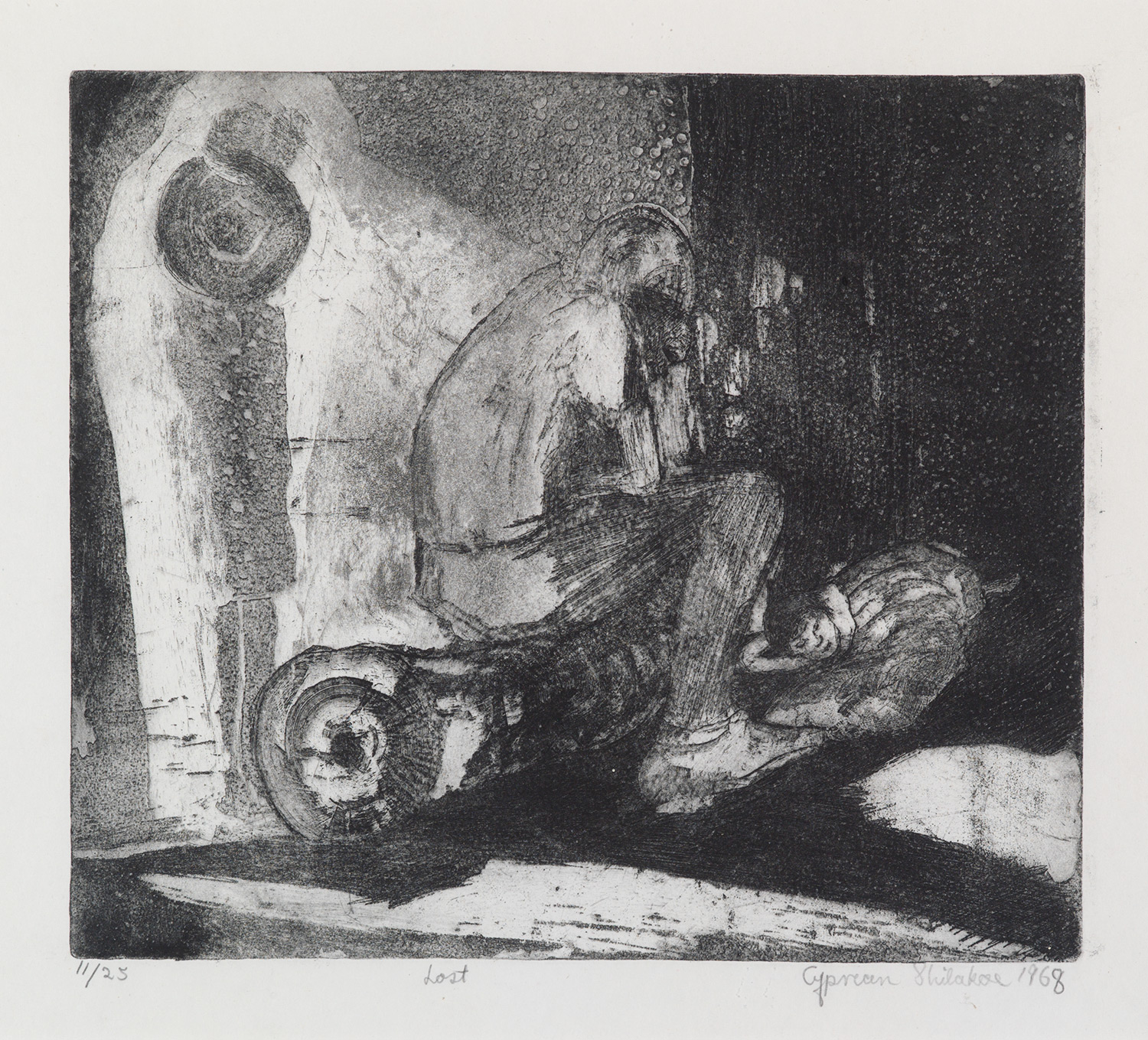

Mpho Lost

1966

etching

edition 11/25

23.5 x 27cm

Characteristically indistinct, the outlines of forms are purposely blurred and indistinct in this work, which captures the isolation and intensity of loss. An illuminated figure appears to watch over the central figure who is doubled over in anguish.

‘Shilakoe’s restraint from direct reference to the oppression of apartheid, and his embrace of wider human frailty, charges his prints with a relevance that reaches beyond the townships of the 1970s to reference universal human experience,’ writes Philippa Hobbs in the catalogue that accompanied the exhibition ‘Cyprian Shilakoe Revisited’ (2006 – 2008).

SOURCE:

http://www.tatham.org.za/cyprian-shilakoe-revisited.html

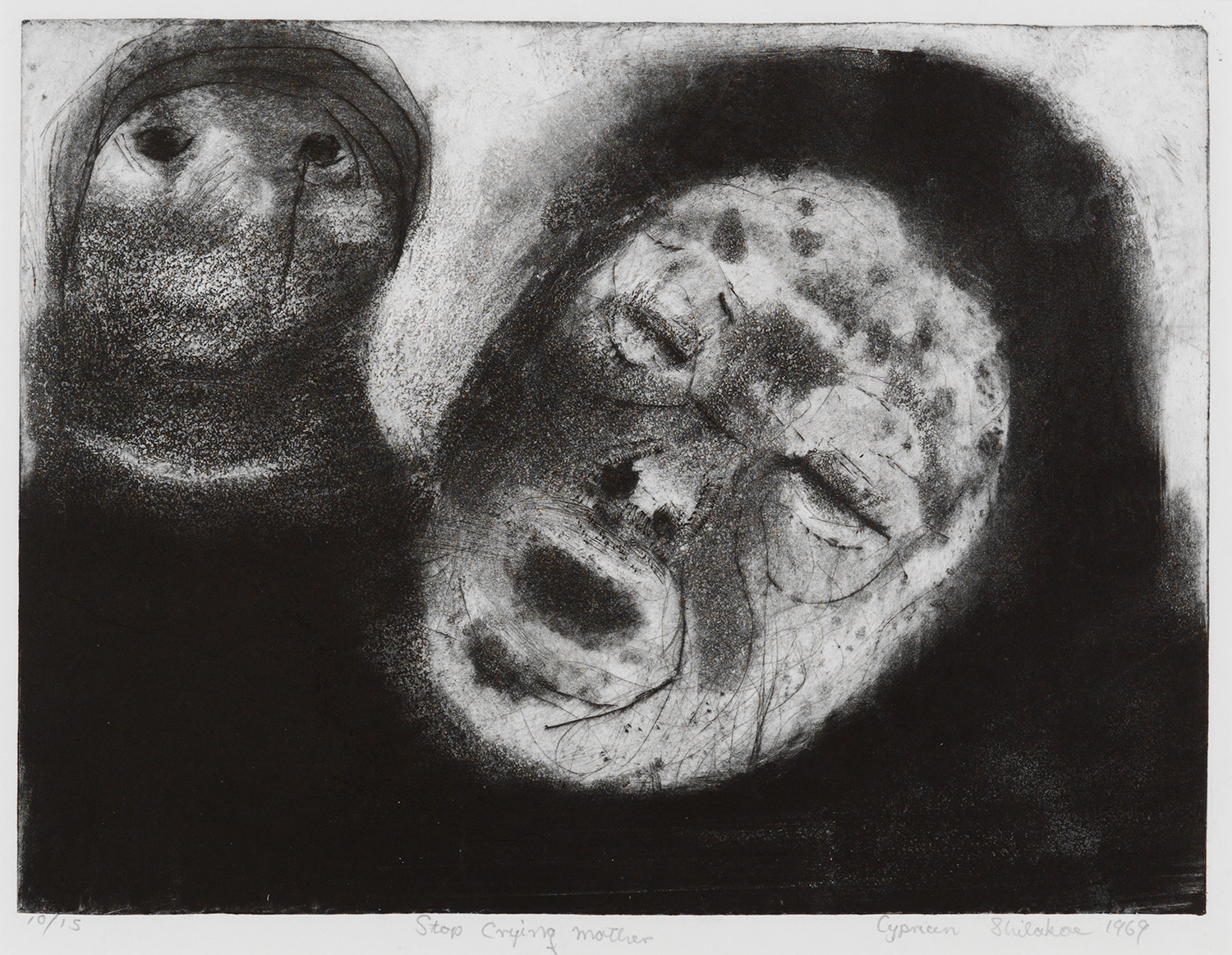

Stop Crying Mother

1969

etching

edition 10/15

23 x 31 cm

This work features two figures joined together in sorrow, the most distinct markings drawing attention to the lines in their faces and the tracks of their tears. The mournful atmosphere and misty, ghostly atmosphere is typical of Shilakoe’s oeuvre. There is a haunting, spiritual quality to his etchings.

Writing for Revisions: Expanding the Narrative of South African Art, Joe Dolby observes that:

… his work has a profound visionary quality. The atmospheric, dream-like effect… is achieved by Shilakoe’s masterly use of aquatint. Instead of using it in large, tonal areas, he preferred to apply the aquatint selectively, resulting in the rich, lustrous quality of… Continue Reading

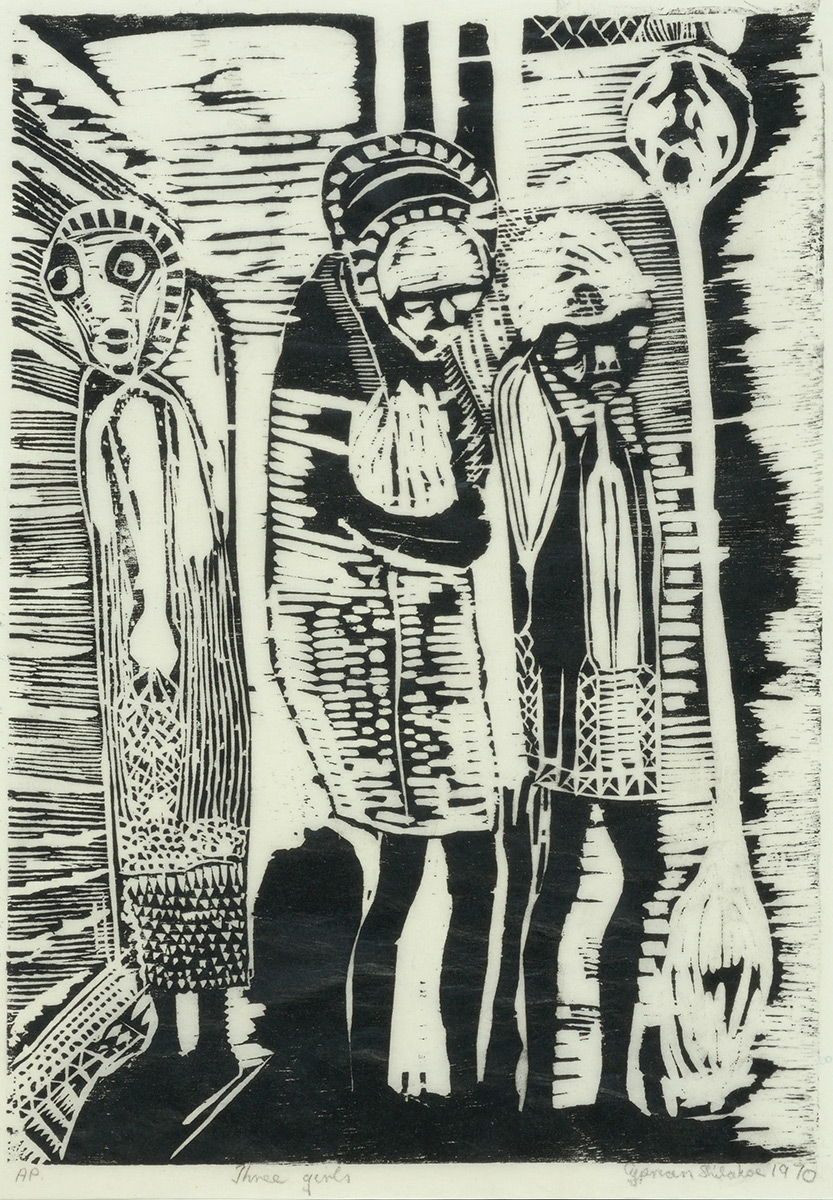

Three Girls

1970

woodcut print

edition AP

47 x 32.5 cm

The influence of Otto Lundbohm, Shilakoe’s Swedish teacher at Rorke’s Drift, might be traced in the technique of this boldly expressive, rough-hewn woodcut depicting three girls and a strange spoon or oar-like shape.

‘The earliest print technique, woodcut first appeared in China in the ninth century. Arriving in Europe around 1400, it was originally used for stamping designs onto fabrics, textiles, or playing cards. By the 16th century it had achieved the status of an important art form in the work of Albrecht Dürer and other Northern European artists.’

Stylistically, this work recalls German Expressionist woodcuts. ‘The 20th-century German Expressionists sought to revive the rich heritage of the woodcut and adopted it as a primary artistic vehicle. Their starkly simplified woodcuts capitalized on the medium’s potential for bold, flat patterns and rough hewn effects.’ Yet this work by Shilakoe is also distinctively African, particularly in the depiction of the abstracted faces of the young girls, which recall African masks.

‘The interaction between the Swedish, American and South African teachers and the black South African students at the ELC made for a complex set of artistic exchanges and cross-cultural influences. The exact nature of the influences brought to bear would obviously have varied depending on the particular teachers. However it is a recurring phenomenon that white art teachers from Europe and South Africa, working in the African context, often insist that they have imposed as little as possible and concentrated on teaching technique, “allowing natural talent to surface”.’

SOURCES:

http://www.moma.org/explore/collection/ge/techniques/woodcut.

http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/rorkes-drift-art-and-craft-centre.

BIOGRAPHY

Cyprian Mpho Shilakoe was born at a Lutheran mission near Barberton. He attended a mission school at Bushbuckridge, and moved to Johannesburg in 1962.

Shilakoe studied under the mentorship of Azaria Mbatha at the Rorke’s Drift Art Centre (1968–9) and was the first student to excel in intaglio printmaking. Embracing themes of loss, longing, and the mystical, his emotionally charged and otherworldly imagery grapples with the fragmentation of family and community life.

Shilakoe set up a studio at St Ansgar’s, a Lutheran mission station near Roodepoort, with a printing press acquired with the help of Otto Lundbohm. He had a close working relationship with Dan Rakgoathe and produced wooden sculptures as well as etchings. His first exhibition was the Goodman Gallery in 1970.

According Rakgoathe, Shilakoe’s inspiration came from clouds moving across the sky, wind in the trees, stains, splashes of paint. In these shapes he could see forms that suggested loneliness, poverty, broken promises and grief. Shilakoe worked mainly in black and white, using different kinds of printing. He explored the techniques of etching, using soft, painterly, blurred aquatints. He seems to allow his images to grow out of the darkness.

He died in a car accident in 1972 just as he was about to be awarded first prize in printmaking at an exhibition at UCLA (University of California Los Angeles). In his tragically short artistic career, his output was enormous – he produced about 80 prints and a number of wooden sculptures within the space of about three years.

In 2024, a powerful exhibition called They Came and Left Footprints, featuring works by Shilakoe and Lucas Sithole (from the Homestead and Bruce Campbell Smith Collections), took place at the Norval Foundation in Cape Town. The title of the exhibition is from a message carved into a sculpture by Shilakoe that speaks of his ancestors who have passed away, reminding us that although they are gone, they have left marks on the world. This idea of footprints symbolises how we are all temporary and how we are remembered by those who come after us. Both artists were active during the 1960s and 1970s, a challenging period in South Africa, shaped by the harsh truths of apartheid. Both were featured in the pivotal 1988 exhibition, The Neglected Tradition.

From 2006 to 2008, the exhibition Cyprian Shilakoe Revisited travelled to ten South African art museums, including The Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Museum, The South African National Gallery, Tatham Art Gallery and Johannesburg Art Gallery. The exhibition showcased a substantial body of the artist’s prints, sculptures and paintings, as well as eight early works never before shown on public exhibition. In preparing for the exhibition, curator, Jill Addleson, together with Phillipa Hobbs (Curator of the MTN Art Collection), travelled to Dennilton to meet with the Shilakoe family. In the family home, they discovered two clay sculptures, two acrylic-on-masonite paintings completed when Shilakoe was training at Rorke’s Drift, and three wood sculptures. A comprehensive catalogue was published in tandem with the exhibition, featuring essays by curator Jill Addleson, Linda Givon, Philippa Hobbs, Otto Lundbohm, Elizabeth Rankin and Yvonne Winters.