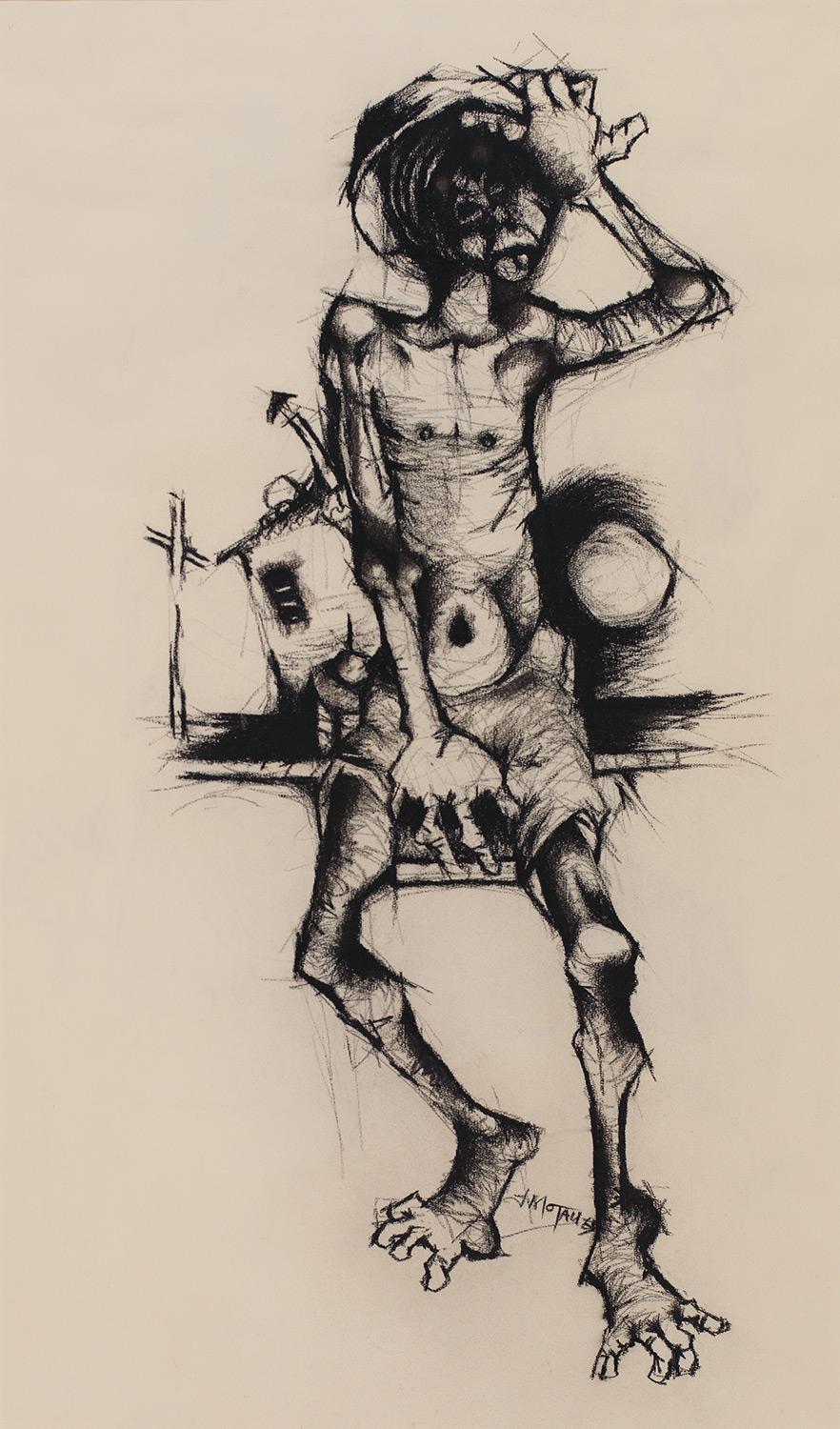

Julian MOTAU (1948 – 1968)

Emaciated Miner

1967

charcoal on paper

100 x 75 cm

This visceral charcoal drawing by Julian Motau depicts a near-naked man. Rendered with nervy lines of black charcoal, his body appears to have been reduced to sinew and bone by hard labour on the mines. He holds one hand to his head in exasperation and the other to his groin in a fundamental gesture of self-protection. In the background, we see the corner of a shack, the full moon and a street pole, which could be read as a Christian cross – only very ironically though, as there appears to be no salvation or mercy here. You can almost hear the wail of the bull emanating from this painful, expressionist work by Motau.

This work was included as part of Yakhal’Inkomo [‘the bellowing bull’], an exhibition co-curated by Tumelo Mosaka and Sipho Mndanda (with Phumzile Twala as research and education coordinator) at the Javett Art Centre at the University of Pretoria in 2022. The exhibition’s title was drawn from a 1968 jazz anthem by the saxophonist and jazz composer Winston Mankunku Ngozi. It refers to the fundamental role of the bull in African life, symbolising spiritual passage, awakening and resilience, as well as material wealth, strength, collectivity and community. ‘Ngozi’s anthem delves into the Black psyche and conjures up feelings of deep remorse, anguish and anger. But it is also a testament to the strength and resilience of creativity in the face of grief and dispossession,’ reads the exhibition statement.

BIOGRAPHY

Julian Motau grew up in a rural homestead in Tzaneen in Limpopo Province. He was almost entirely self-taught. In 1963, he migrated to Johannesburg where his rare talent was quickly recognised by artist Judith Mason, who provided him with studio space and mentorship.

In 1967, at 19 years old, he had his first solo exhibition at the Goodman Gallery and in that same year won the New Signatures exhibition in Pretoria.

In a tragic twist of fate, Motau was murdered in the Alexandra township just a year later.

Strongly influenced by the uncompromising expressionism of Dumile Feni, Motau’s artwork is remarkable for its intensity of expression and the anger which comes through in its choice of subject matter. Motau has been hailed as marking a new politicisation of township art, but while there is some truth to this, the work remains too unruly and too unformed to constitute much more than an interesting beginning, tragically curtailed.